This is really just for a friend on Facebook who knows someone who’s learning Python, but I thought I might as well put it in the world. I think a lot of beginner tutorials for Python start you off on the wrong foot—they recommend a second-rate editor, or start off with bad practices. Here’s my list of ways to get started on the right foot. This is aimed entirely at Windows users.

Step 1: Install development tools

Windows has a tool called winget which saves you a lot of browser clicking to install the tools you need. Right-click the Start button and select “Terminal (Admin)”. Paste in these commands:

winget install --id=astral-sh.uv

winget install Microsoft.VisualStudioCode

winget install Git.Git

Close PowerShell. Note that you don’t need to install Python—uv does that for you when the time comes.

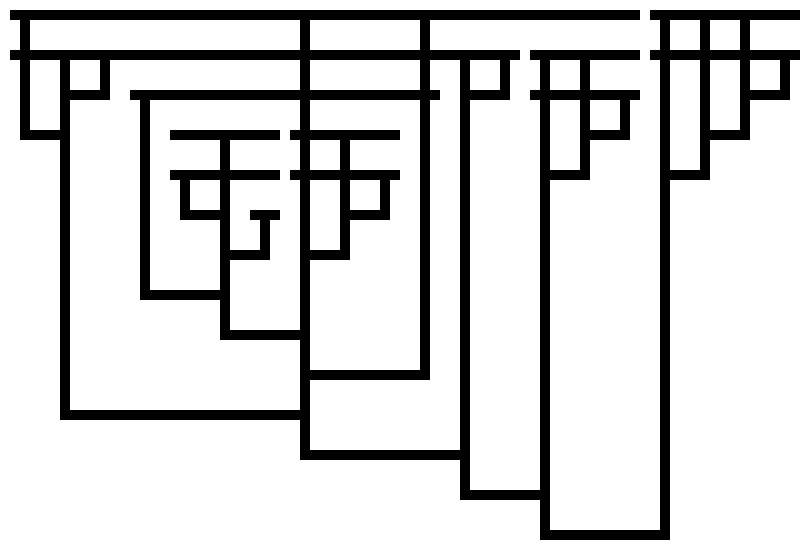

Step 2: Start VS Code and create a Python program

VSCode should now be in the Start menu; start it and maximize it. Select File > Open Folder… to open a folder (or press Ctrl-K Ctrl-O). We want to create a new one, so click “New Folder”. Let’s call the new folder “first-python-project”. You are the author and the folder is empty, so select “Yes, I trust the authors”.

We need to set this folder up for Python programming, so select View > Terminal to open a terminal, and enter the below.

Wait for that to finish. Now go to File > New File… and create a file called hello.py. The .py extension tells VS Code that this is a Python file. Once you’ve created it, you’ll see a prompt asking if you want to install the recommended Python extension—say yes. Enter the following short program.

Step 3: Run your program

Make sure hello.py is open in the editor. Click the “Run Python File” button (▶️) in the top-right corner of VS Code. VS Code will take a moment to understand your Python setup, but soon you should see your hello world message in the terminal at the bottom of VS Code.

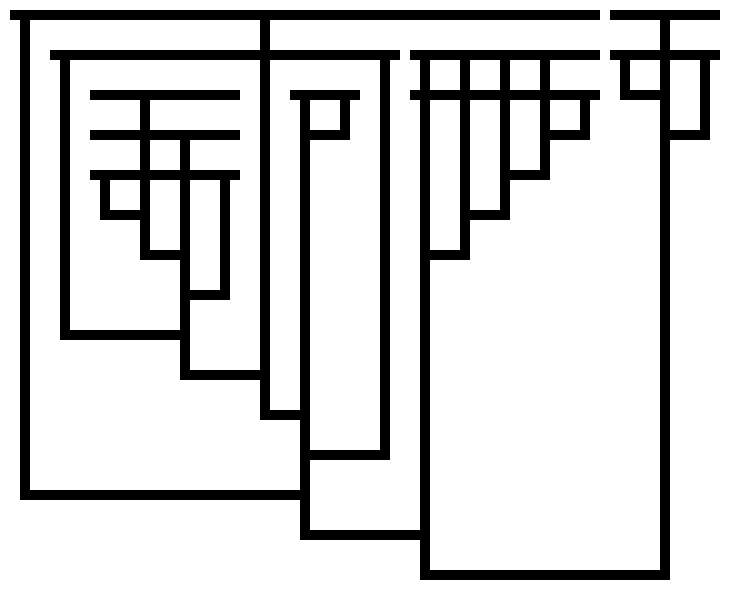

Step 4: Save your work with git

Professional programmer advice: programmers use version control to make a record every time they get something working. Select View > Terminal to open a terminal, and configure the version control system Git with the metadata about you that should accompany the work you do on your program, so you get credit/blame for your work:

git config --global user.name "Your Name"

git config --global user.email "your.email@example.com"

Down the left hand side of the window, you should see various icons including a magnifying glass. One of them will be a kind of branching structure, and if you hover over it, it says “Source Control”. Click on this, or press Ctrl-Shift-G. You’ll see “pending changes” – this will include your new file hello.py as well as several other files that are there to manage your Python environment. You want to save them all. Hover over the bar that reads “Changes” and click “+” to “stage” your changes. In the “Message” field at the top, write a message like Wrote hello.py and press Ctrl-Enter. Now your changes are saved—if you break something, you can see everything you changed in this view.

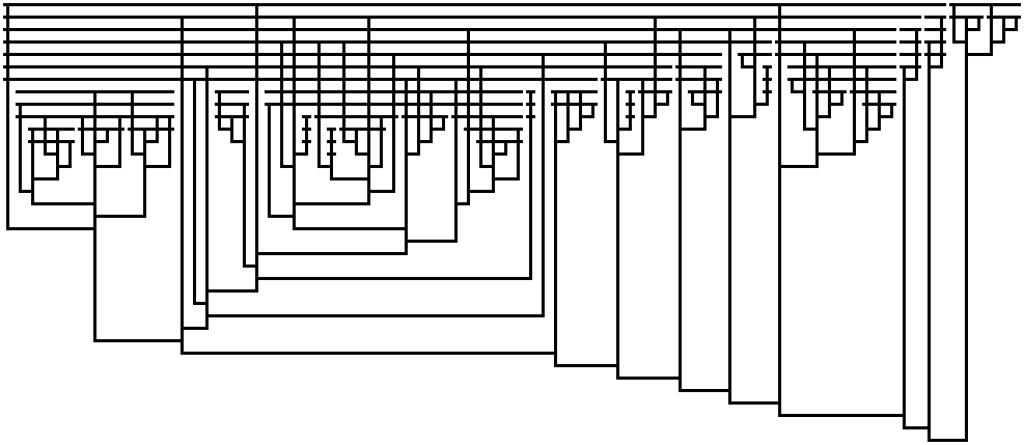

Step 5: Add an external library

Much of the power of Python comes from the many modules that already exist for various jobs. A lot of good modules are bundled with Python, but zillions more are out in the world waiting to be used. Let’s use one: the “requests” library, for accessing stuff over the web. Go to View > Terminal and type

This updates your pyproject.toml file with the new dependency. Let’s write a program that uses it: select File > New file… and create a new file called joke_fetcher.py with this code:

import requests

print("Getting a programming joke from the internet...")

joke_api = "https://official-joke-api.appspot.com/jokes/programming/random"

response = requests.get(joke_api)

joke_data = response.json()

print("Here's what came back from the API:")

print(joke_data)

Run your joke fetcher using VS Code’s run button: make sure joke_fetcher.py is open in the editor and click the “Run Python File” button (▶️) in the top-right corner. A joke, probably extremely weak, will appear in the terminal window, with a setup and punchline.

Something is working, so let’s save your work again: go to the Git view as before, put Add joke_fetcher.py in the “Message” field, and press “Commit”. It will complain that you haven’t staged anything; just say “yes, stage everything” and commit. Now you have a record of your whole project, both before you added the joke fetcher, and after.

Professional programmer advice: because you used uv to install requests, it’s recorded in your source code that it’s needed. specifically in the file pyproject.toml. If you give someone else your source code and they run it the same way, “requests” will be fetched automatically in order to run your program—the same version of “requests” you used, and indeed with the exact same version of Python. A lot of what we do in software development is there to avert the ancient, sad cry of “well it works on my machine…”

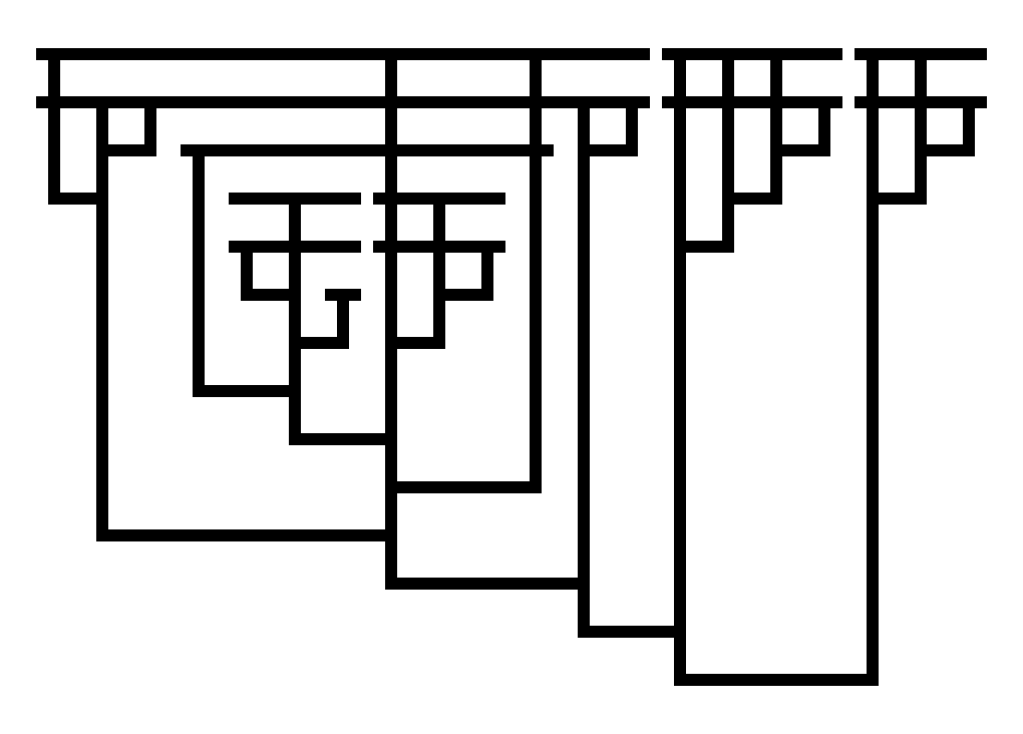

Step 6: Install and use GitHub Copilot

AI programming assistants are not reliable, any more than human programmers are, but they can save vast amounts of time and frustration. I am aware that the world is full of people who pooh-pooh them, but they are wrong and I recommend installing one right away. The easiest one to install is GitHub Copilot using ChatGPT. Click on the Copilot icon in the bottom bar (a kind of chipmunk with Mickey Mouse ears) and select “Set up Copilot”. You’ll need to create an account on GitHub, and choose a name for the account; every programmer needs a GitHub account so this is no hardship. The free tier gives you 2,000 code completions and 50 AI chats per month. Here’s what it’ll give you:

- Code suggestions: As you type, Copilot will suggest completions. Press

Tab to accept them

- AI Chat: Press

Ctrl+I to open Copilot Chat and ask questions about your code

- Explain code: Highlight code and ask Copilot “What does this do?”

Try asking Copilot: “How could I get just the joke text instead of all this JSON data?”

Upgrading Your AI Assistant

Once you start coding regularly and want more AI help, consider these upgrades:

- GitHub Copilot Pro ($10/month): Unlimited completions and access to better models

- Claude Pro (£18/month): Conversational AI tutor that’s excellent for learning – access via Claude.ai or VS Code extensions

- Claude Code: runs in a terminal and helps look at your whole codebase.

- Cursor Editor: Popular alternative to VS Code with built-in AI features

Start with the free tools, then upgrade when you find yourself hitting limits or wanting more capable AI assistance.

Other things to try

- Ask Copilot to help you parse the JSON to show just the joke

- Look at PyPI for packages you can use with

uv add

- Uh actually learn Python I guess

- Good luck!